After a few years in freelance art, I’ve compiled a few thoughts on how to sell more of the original wildlife art you’ve been working on. (Strap in! As can be the case, this is fairly long…)

Perhaps some is collecting dust in the “spare” room that once held more interesting plans than an “art loading bay”? Your own walls would be a great place for such “storage” (and decoration) for the time being, if you didn’t worry it might give guests the impression you were stroking your insufferable ego?

I can relate to all of it and more. I currently have about 15 framed pieces sitting in my new “office” (read: spare room at my parents’ house). Some I now regret making, as the subject matter barely resonates with anyone. There are a few older works which are frankly mediocre, and I’ve had trouble selling them regardless of asking price.

The remaining ones I have to believe are still just waiting for their moment. The right day, in front of the right person, who’s in the right mood and had the right breakfast. If they happen to have won on the pools yesterday, that’s also no bad thing. Sales on a speculative basis often boil down to these “lightning in a bottle” moments.

So, I’ll preface all this with a healthy injection of self-awareness. Straddling the bounds of an online and “in-the-flesh” presence, I continue to explore new methods. I don’t have all the answers; I’m constantly building knowledge for the future. I can happily pass on what I know, while continuing to enjoy the occasional surprise sale of a piece I’d all but condemned to the archives.

This is by no means an exhaustive list. I’ll try my best to include ideas landing outside my range of personal experience, through having observed other people’s success. No single avenue is necessarily the “Holy Grail”, and it would be ill-advised to rely upon one alone.

The main message is to combine as many of them as your investment of time, energy and funds will allow.

I have been prone to believing that fiddling around with my website, spending time brainstorming, scheming or researching selling options is skirting around the “production” side of my job as an artist, and I’m wasting a lot of time. This is damagingly false. All of the above is essential work.

Key tip: If you don’t believe that the sales side of things is the “real work”, change your mind. If you aren’t “sales-minded”, change your ways.

Drawing/painting is a great part of your job, but sales is at the centre of it. If you don’t sell enough of your wildlife art to earn a living, you have a hobby.

Anyway, let’s talk about the origin of everything…

The wildlife art you choose to make

If you just can’t resist tackling that goblin shark in an abstract style using only fluorescent yellow and green, knowing you may not find a buyer and it’s all purely for your enjoyment and ownership, then of course, “more power to you” as they say.

However, the wildlife art you make, you want to sell, which must be why you’re still reading. That’s the qualifying condition of this blog. First important point; damage control. Focus on the art you still haven’t made yet, and do your damnedest to avoid adding to your “unsold” inventory.

After Brexit, a global pandemic, and a cost of living crisis, life hasn’t exactly been plain sailing for artists in recent years. Traditional art is hand-hewn, considered work. In the age of mass production, luxuries like this only sit within the means of a relative few.

However, to quote my framer, “there’s always money lying around, and money follows quality”.

Money follows quality. If you take nothing else away from this blog, let it be this:

To maximise your chances to sell from the gun, make the very best wildlife art you possibly can.

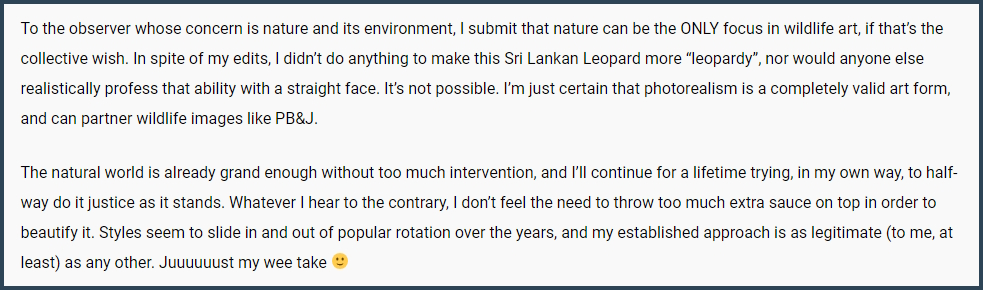

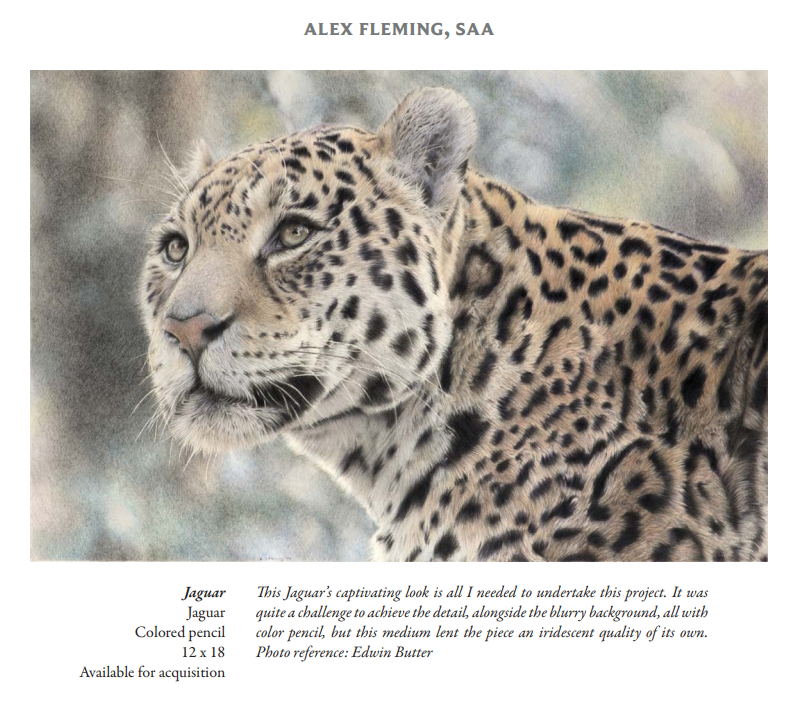

No genius strategy will help close the sale on something wholly unappealing. What qualifies as “worthy” art is subject to the eye of the beholder. I’m delighted to say that enough people enjoy realism for some to invest in my work. Of course, realism isn’t the only show in town. (Many people argue with conviction that realism shouldn’t even be in the conversation!).

That said, we all know a few immutable truths.

- A compelling composition draws your viewer in.

- Balanced colours and values please the eye.

- Artwork of “big cats” is more commercially viable than that of Hercules beetles.

- Collectors greatly appreciate archival quality materials, and…

…good technique will result in higher quality work, regardless of your chosen style.

Go to YouTube, Patreon, Domestika, to get your hands on some solid advice and walkthroughs on all of the above. These are some of the core variables under your control, so make sure they “go up to 11” (and if you got that reference, you’re alright by me). This is all especially important if you lack sales skills, comfort around strangers, or “gift of the gab”. Once again, I can relate.

[Personal circumstances mean I’ve never had the wealth of time needed to put together an online channel brimming with all of this advice, but my newsletter, sent every couple of months, does include the odd tip. Every issue includes something new, with a “throwback” tip from the same month of years past. So after six issues, you’ll have had access to all of them. Feel free to sign up here if this is of interest to you.]Additional pointers

- While making the best wildlife art you can, ask yourself how unique it is too. If you have at your disposal a good quality camera, and if you’re fortunate enough to own a good range of lenses, you can head to your local zoo, and put a day to very good use taking your very own pictures. If you have the means, you can head off to some exotic locations to take your wildlife reference images to the next level (I can dream a dream!). There’s both an upside and downside to the well-worn path of using popular images (royalty-free and paid). They’re popular because they resonate. Maybe they’re irresistible. However, they can also become stale. I suppose your buyer may not have seen all the other renditions of this “must use” image, but if you can confidently say there is absolutely nothing like the original piece of work you made, and better yet, you’re the one who took the source photo, then added value is a guarantee, and your signature marks this work as a genuinely personal piece through and through.

- It’s worth thinking ahead about finite projects, and themes to tie all pieces in that project together, rather than a disconnected, endless “conveyor belt” of wildlife art, which can be a little much to take in at once! You can sub-divide your work into species, environments, a theme centred around the play of light, or even dominant colour. I focus on continents, with a separate “Home” series of large pastel works whose focus is mainly the natural environment, but with a subject at the heart of it. I bump up charitable donations considerably from my standard 10%. I’m really proud of what I’ve done so far, and looking forward to adding to it. I guess this series will be my legacy!

- Title your work thoughtfully! I have started naming my pieces a little more imaginatively, after years of defiance. I don’t think I was patently wrong to give names such as “Sumatran Tigress” to my work. I had good reasons that made sense to me, and fit in with some of my values as a realism artist. But I absolutely was not entirely right, since sales were on the line, and one could argue these titles are quite dry. A good title can work wonders in helping sell a piece of work, and it really isn’t much effort. Consider your title as you work! How do you feel about your art? What word(s) would encapsulate this eagle in flight? If you read often, you’re likely armed with expressive, poetic or simple words and phrases. If they pair well with your work, you can evoke an appropriate emotional response in your buyer. This is key: Emotion can sell wildlife art! Tap into that to see an instant uptick in interested buyers.

Sell your wildlife art

Open call exhibitions/competitions

I can’t say whether years worth of padding out my website with accreditations has indirectly resulted in more sales. I suppose it can’t have hurt! I’ll say candidly that I did actually aim for awards at one point in time. All to “boost the CV”, harbingers of relevance and recognition, evergreen “seals of approval” by the industry. I do still struggle ethically with the “gatekeeper” aspect of things, and the years of rejection and expensive entry fees. I suppose one or two open calls ended up fitting me well. However, to have found them at all was only through giving a few of them a shot. The two I enter regularly are:

DSWF Wildlife Artist of the Year

They both welcome (and help you sell) high quality wildlife art. The former announces by email that submissions are open. You just need to register your interest, on the right hand side of the home page. The latter favours art which tells a story. The only one I tell is immediately observable, with no subtext; my art is my best attempt to express the sheer beauty of nature, in all its detail and vibrancy. The kicker is that DSWF is a charity, directing a large portion of sales and entry fees to their ongoing wildlife projects around the world, so I’m very happy to keep entering this, accepted or not.

There are, of course, other open call exhibitions, such as by the Society of Wildlife Artists. Alternatively, medium-based ones are available (relevant for me would be that hosted by the Pastel Society). The reasons I don’t enter these vary, but usually it’s because my style of art doesn’t fit in. Most open calls express what they’re looking for, often with a marked aversion to realism, so if you’re rejected on the strength of this before the judges can even consider the quality of your work, don’t be too browbeaten. Just make sure you read all the guidelines thoroughly.

The open call events accepting me allow me to sell my wildlife art. They can also lead to continued relationships with collectors. This route can be quite a long and windy path to regular sales, so I can’t advocate universally. I’ll simply advise those who are keen to proceed with both caution and a strong mind.

Associations and societies

This is a recommended way not only to gain regular access to exhibitions and prospective custom (often with no qualifying criterion except for your membership to be paid and in good standing), but also to increase your industry contacts, and to engage with other like-minded artists. And of course, to sell your wildlife art.

“No man is an island” – thankfully peers I’ve had the pleasure to meet share a “feast mentality” regarding opportunity, business potential, and the dispensing of whatever experience they’ve accrued over time. We’re generally a very helpful bunch, all knowing the struggles and pitfalls. It’s nice to immerse yourself in such a community, at least to some degree.

At the time of writing, I’m a member of the Association of Animal Artists (UK), the Society of Animal Artists (USA) and King Street Studios (Lancaster, Lancashire). AAA has a biannual exhibition, and holds weekly zoom video calls, which is especially helpful when feeling a little starved of human contact! SAA offers a juried submission process twice a year, assigning membership statuses to those accepted. KSS is my jump-off point for any opportunities coming up in or near Lancaster. This is the strongest “art scene” near me for many miles around.

Others include the Society of Wildlife Artists (UK), The Wildlife Art Society International (UK), and many more around the world.

Trade shows/fairs

This one’s largely beyond my scope of experience – I’ve actually only done one! There’s a lot to it, not least the hiring costs of a stall, which can run into the hundreds, and the waiting lists can be very long, depending on how prized an event you’re hoping to attend. You often need to source your own table and chairs, shelter, stands, panels, racks, print browsers, banners and card payment machine.

If you can neither afford all of this nor have anywhere handy to store it, the venue itself may allow you to hire some equipment, which is especially useful if you’re just trying it all out. Planning a show or fair involves graft, and I’m sure many problems are only anticipated once one’s experience broadens.

If you’re a “people person”, events like this are probably right up your alley, and particularly worth pursuing if held repeatedly. Local markets are often held every month, and bigger events elsewhere usually happen annually. As with all selling environments, you won’t necessarily be successful in sales on your first outing; very few people, if any, will know you yet, so again, don’t be discouraged by this.

Repeated outings will help foster recurring contact with prospective customers, and since the majority of those you convert must know, then like, then trust you, it’s highly advised to weather those first few times where you end a very long day by bringing most of your wares home. Stay the course, keep chatting to the regulars and discover what they like. You can build a profile of your ideal customer, and what kind of wildlife art you can really sell.

On the day itself, give yourself something to do that keeps you available at the drop of a hat, neither glaring at passers-by, nor being totally closed off to them. Keep everything conversational and be friendly, without pushing sales. Treat it as nothing more than a day out to begin with – you’re just trying to be an affable presence first, a familiar face second, and a trusted vendor third.

3rd party platforms

I’ve become very cynical over time about the unilaterally applied model for seemingly everything online: create something appealing for free, amass millions of users, encourage its use for business, make those users dependent upon the platform, sell advertising space, throttle organic reach, and offer the most exposure to the highest bidder. Sweet, naïve Alex of 2012 – how little I knew at the time!

Having said that, if you’re someone who enjoys business success through social media, I’m genuinely really pleased for you! That’s just proof you followed all the logic of the ever-changing algorithm, recognised it as part of your job, did the hard work creating all the content that fit the mould, and hopefully you’re reaping consistent rewards. I just never had the strength to do things “properly”. Nothing I’ve done on social media has been big or clever, and I’ve been burdened with more than a smidge of contrarian defiance and cynicism about the whole thing!

However, just look at the numbers. I said millions, we’re realistically talking billions. This is clearly an environment with huge potential to sell both original wildlife art, and reproductions. That’s if you can stomach it, and however despairing you might feel about their paywalls! Advertising on such a scale is fertile ground for A/B testing (showing two different versions of your advert to a split group, or the same advert to two different group types, finding which one works better, and repeating the process until you’ve really refined your copy and images).

Don’t just think social media – there are retail outlets like Redbubble and Etsy. Saatchi Art is especially prized if selling originals. All of these offer plenty of potential for you to sell wildlife art. The big win is when you drive your following to these sites, and increase business that way.

Your website may be set up for selling, charging only annual web hosting and domain renewal fees. So, why is all of this 3rd party stuff worth bothering with? For starters, of course, many users of the 3rd party retailer would never know of you without your presence there. Also, some of your existing followers or even customers may prefer it, either because they already have an account with them and the transaction is a little easier, or purely due to implicit trust from the outset. You’re not out to swindle anyone of course!

But on Etsy, for example, there’s a standard procedure for anything that goes wrong, and sellers on these platforms live and die by their reputation, which they build only through regular sales and reviews. A seller can upload to their website only the favourable testimonials, so the passing observer may not be able to discern a genuine person from a charlatan, without some kind of broader touchstone for trust and confidence, as provided by a bigger marketplace.

Brick and mortar galleries

Treat gallery representation very carefully. Be sure to have a portfolio of your very best work ready, as the standards are usually very high. Don’t forget your own standards, too, so treat your interaction with the gallery owner as you would a job interview. You’re not just sitting across from him/her praying they accept you, and your work to have finally “made it”. This is your opportunity to find out if the gallery fits you.

If you reach a dialogue, make sure you visit them at least a couple of times. Get a “gut feeling” about the art you see, the venue, the location, the customers and the owner. Does their website list works that have sold, and how recently? Are they selling new works often?

When presented with terms, read them thoroughly. If something doesn’t feel right, ask for clarification. If things still don’t feel right, walk.

Some galleries impose the condition of “sale and return”. Under this stipulation, they can return, at any point, any work that hasn’t sold. It’s then your job to sell your wildlife art some other way. This is very common, and in my opinion, totally fair. It’s a healthy reminder that part of your job as an artist is to make some very sellable art. Once you pass your work to the gallery, there’s only so much the gallerist can do to make the sale.

Others may demand you provide a certain number of works per month. Of all things I’ve encountered, this is the most arbitrary, soulless and ludicrous of impositions. To me, selling art as a time-sensitive “unit” feels like anathema to the industry itself, leading to burnout in artists, and destroying the joy of creation. You can even see it in the work sometimes – if there’s no magic, or you can’t instill a personal “calling card”, what’s the point? Art is not a commodity!

That’s one reason I turned down a contract from a large commercial gallery a few years ago, requesting exactly this. Something in my gut was off, and I didn’t have the experience to be totally sure why. The longer I left the thoughts to ripen, the more sure I was that I’d made the right decision. On top of this, “sale and return” is often imposed. I can only imagine the pressure to constantly sell all of my wildlife art come what may!

Save the phone call and in-person visit for later. In this day and age, I feel it’s more convenient, appropriate and professional to send an initial email. It’s less pushy, doesn’t catch anyone off guard, and allows a little time for your presence to mature slowly. A little checklist for you before you submit:

- Be sure your targeted gallery has explicitly said on their website that they accept email submissions.

- Include a very brief bio (or attach a CV), which mediums you use, and a very small handful of images of your best work.

- Don’t inundate them with attached images.

- Avoid including a long list of accreditations in the text body. The gallery knows exactly what they’re looking for, and blowing your own trumpet is rarely a good thing.

- It’s best instead to have a website ready, with links to the relevant sections (portfolio, accreditations, “about”).*

- Sign off by prompting an action (“I’d love to come and visit, if you’d like to see more of my work in the flesh”, or simply “I look forward to hearing from you”).

Don’t pester the gallery if you don’t hear back. You also don’t need to wait to hear from them before you ask another venue. Again, treat it like applying for a job. To that end, unless the terms of one gallery state that your representation with them is exclusive (which would be extremely rare), multiple venues can represent you. If you make it into two galleries, you may have doubled your chances of selling your work through this channel!

If do you strike up a promising and cordial relationship with your gallery, it could also talk a while for you to learn about appropriate pricing. What wildlife art sells, and when does it sell? The general rhythms of everything on that side of the art industry will come in time. You’d be remarkably lucky if everyone instantly fawned over your work as it stands. You may have found common ground in general with the gallery owner about your passion for wildlife art, but even so, it would be wise, to a degree, to start tailoring your output to what you know is popular specifically among the gallery’s patrons, and you’ll only learn the finer points of this over time.

It’s not a question of surrendering your entire style and specialty for the sake of sales. It’s more accepting there’s bound to be a little “push and pull”. Where you feel your calling is African wildlife, you might end up being the local “go-to” barn owl artist too (a mighty popular subject after all), and you may love this new direction! You don’t have to let anything define you, but letting a misplaced, stout sense of pride get in the way of sales is to ignore the practical realities in front of us.

Sell wildlife art privately (no 3rd party)

I lied earlier – there is, in fact, an art sales “Holy Grail”. No middlemen, no compromising on how you want the interaction to go – all an unadulterated connection with your buyer, who knows, likes and trusts you so much they’re very happy to go directly to you, with no qualms about what you’ll deliver. It’s the ultimate freelancer’s sanction. No helping hands, sponsorship, converting “cold leads” or having to pad out your list of accreditations. Someone thinks you are absolutely enough as you are, and worthy of your status!

One of my early goals was to build a strong relationship with a small handful of avid collectors. I’d work away quietly without banging my own drum constantly in an already saturated marketplace. I’d make enough money to live happily in a comfy chair, book in hand, with an adequate supply of coffee, cheese, bread, beer – all that unhealthy stuff I live for. I’m lucky to have come a little way towards this, but I very much doubt I’d ever get there entirely.

Your best opportunity to grow your base of private customers is by showing them you care, and treating them well! When your customer’s experience is underpinned by an undeniable “wow” factor, they’ll be proud to recommend you to like-minded people.

Also, if you haven’t created a newsletter yet, do so today! Those who subscribe show signs of being your biggest fans, and a handful of them really will be. Here, you can reward your audience with your best resources, advice and product offers, while really peeling back the curtain on your life as a freelance artist. You will sell your wildlife art to the very, very keenest among them.

“The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley”, so part of a career in art is accepting you will likely have to “pay the piper” in some form or another for a very long time, be it through advertising, a gallery with its hefty commission, a social media circus, countless 3rd party retail outlets, or consistent applications and travelling to shows, events or competitions. In fact, it’s a great idea to keep a few irons in the fire anyway, so that if the sands start shifting down one avenue, you’re a little more “antifragile” by being able to head further down another. So, hedge your bets and move slowly. Moderation is the answer to almost everything (a lesson I’ve learned the hard way too many times in life!).

It’d be foolish to close off all bar one avenue of opportunity and income – a sudden downturn in business would leave us dangling. Take this particular example – the close circle of collectors. Nobody will collect forever, and none of us can reasonably expect income sustainability to pivot around such a small and especially fragile idea.

You may have commissions to fall back on, and you may not. Competitions and shows may reject your work, online sales may drop, social media may decide to throttle your levels of exposure, and as nice as the alternative would be, there simply aren’t hordes of people queuing up to bid for your next masterpiece.

Safety really is in numbers, and to not offer prints is a missed opportunity in steady stream income. This blog is already so long, and printing is such a separate topic, that I’d better write about this another time.

A word on pricing

You’ll increase your chances of selling your work by offering it through multiple channels, one after the other. It’s possible for there to be overlap here (Exhibition of Wildlife Art in particular keeps all work listed on their site for a full year after the exhibition itself closes, only asking that you inform them immediately if your work sells elsewhere). If there is overlap, you must price your work consistently, and even if there’s no overlap, keep an up-to-date record of everything publicly available anywhere.

I ran into a little trouble a couple of years ago when one piece sold at a gallery. When the buyer did a little digging, finding out the same piece was also available online at a much lower price, he wasn’t at all happy. Understandably so! It was a listing I’d made of the same work, unframed, on a fee-free website a year or so prior; a listing I’d completely forgotten about. I’d since adjusted the price upon its admission to the gallery, to account for the commission they would later take when it sold, and the pricey framing. Not only did I come across unprofessional, but so did the gallery, and I tormented myself about it for a little while.

I now have a section on my spreadsheet full of information on all my work, stating where each piece was/is, be it in my office, at a gallery, or represented online. As soon as a work budges, I update the spreadsheet. Lots of up-keep, but worth everything being in order, so I don’t make this error again.

If you must have the same piece listed for sale in multiple locations, where possible, just keep the price the same, and accept that your takings may vary greatly, depending on the fees. Make allowances for this in your pricing, and things will even out over time. It’s much simpler this way!

How to price in general…again I’d best write about that another time.

Summary

It’s really worth thinking well ahead about the wildlife art you’re going to make, and make it carefully. Churning out work you’re not completely proud of for the sake of having an extensive portfolio, or a full stall at that art show you’ve pinned as your major event of the year, may see you heading home with lots more storage problems than you started with.

Plan where you’ll try to sell your wildlife art, and what you’ll do if you don’t succeed. I feel it’s much wiser to make a smaller number of truly considered pieces, and run all of them through as many sales channels as there are at your fingertips. It can feel a little like plate-spinning, but this gives you a much better chance of selling what you make, and keeping the floor of your hallway hazard-free!

If you’ve got any extra methods of your own, or if I’ve forgotten something, please add it to the comments below. Hope you found this useful 🙂

Recent Comments